By Dr. Jody Edward Ginn

April 1, 1934, was idyllic Easter weather in Dallas. 26 year-old Edward Wheeler, a Texas highway patrol officer, and his young wife, Doris, shared a biscuit-and-gravy breakfast and made plans to celebrate after Edward, whom most called E.B., completed his shift on motorcycle patrol that day. Just across town, 22 year-old Holloway Murphy was also up early,excited to begin his first day on the job as a THP motorcycle cop. This would be, he thought,his next to last Sunday living at the local YMCA, before moving into an apartment with his fiancé, 20 year-old Marie Tullis. Marie might or might not have noticed that Holloway placed a handful of 12 gauge shells in his pocket rather than in the chamber of his shotgun; he wanted to be careful about riding his motorcycle with a loaded gun, in case he took a spill and the gun went off, hurting a civilian. H.D. and Marie were to be married 12 days later on April 13.

Both Wheeler and Murphy set about that Easter day thinking that their lives were yet in front of them, not knowing that the plans they were making would soon be waylaid. By mid-afternoon, the two young motorcycle patrolmen, following senior patrolman Polk Ivy, were casually cruising along state highway 114 just north of Grapevine, northwest of Dallas. About 3:30pm, they noticed a lone vehicle, black with yellow wire wheels, parked 100 yards up a dirt road. The patrolmen U-turned their bikes, rolled up toward the vehicle; it appeared that the occupants were stranded and in need of assistance. Polk Ivy continued down Hwy 114 for some distance, until he realized his two junior officers were no longer behind him.

Farmer William Schieffer heard the motor bikes coming from a distance. He had been doing Sunday chores on his hardscrabble lot that bordered the dirt road, and around 10:30am he observed a young couple “necking” in the roadside grass. He was only 30 feet away at that point, hauling rocks from his orchard. The girl was “petite with bushy hair,” and holding a white rabbit in her lap. Easter picnic, he figured. As he pushed his wheelbarrow across his orchard that morning, he watched the couple stroll down to the highway — and back — as if looking for someone.

Now, the day was getting on and Farmer Schieffer’s two daughters came out of the house to call their dad in for Easter dinner. That’s when they spotted the two motorcycle patrolmen stopping their bikes just a few paces from the mystery car. From approximately 100 yards away, the farmer and his daughters—Miss Isabella Scheiffer and Mrs. Elaine Adams—saw the officers dismount and stroll towards the parked Ford. Before the officers could even reach the vehicle, they were abruptly felled by shotgun blasts. E.B. was killed instantly, but Murphy survived the initial volley, falling on his side. Stunned, Schieffer and his daughters watched

both shooters — including the young woman wearing brown riding pants and boots — walk up to the dying man and fire upon him again, at point-blank range. In seconds, two families were destroyed so that Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, two of the most notorious criminals in US history, could evade justice a little longer.

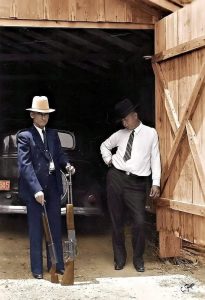

Investigators and others look at the scene of the ambush along Hwy. 114 in what is now Southlake.

Schieffer and his daughters were not the only witnesses that Easter day. Jack Cook, a lifelong resident of Dove Road (who died in October of 2013) saw a young couple, male and female, at the site just prior to the shootings. Shortly after, a Mr. and Mrs. Fred Giggals had been on a Sunday drive along Hwy 114, some distance behind Ivy, Wheeler, and Murphy. Speaking on behalf of his wife and himself, Mr. Giggals reported that they heard the initial shots after they drove past Dove Road and turned around to see what had happened. According to Giggals, he and his wife exited their car briefly and saw what they thought were two men, with the taller

shooting into one of the prostrate bodies. The Giggals were only within sight of the shooters for a matter of seconds, approximately 100 yards away and with their view obscured by grove of trees. Mr. Giggals said the shooters looked over and saw them, at which point the couple beat a hasty retreat to their car and sped away.

*****

The Texas Highway Patrol (THP) was a nascent organization in 1934. After the brutal

execution of Wheeler and Murphy, chief Louis G. Phares took quick and decisive action, issuing a $1000.00 reward for the killers and assigning his entire force of more than 120 officers to search for them. Phares also sought out the services of legendary former Texas Ranger captain Frank Hamer—who, unbeknownst to Phares, was already on the killers’ trail and assigned another former Texas Ranger, THP trooper B.M. “Maney” Gault, to work with him, at Hamer’s request.

By the time Murphy’s young fiancée wore her wedding dress to his funeral, efforts to deflect responsibility away from the killers were already underway. Clyde Barrow himself wrote a letter to the prosecutor in which he placed the blame for the Grapevine murders on his former partner-turned-nemesis, Raymond Hamilton. This ruse was briefly successful, likely because Hamilton was traveling in an identical Ford V8 with Bonnie’s younger sister and doppelganger, Billie Mace. However, they were soon exonerated due to validation of their whereabouts at the time, physical evidence at the scene, and forensic evidence directly linking the true killers to the crime. The Barrow and Parker families also attempted later to recast the blame for the Grapevine murders, albeit in a manner that, ironically, contradicted Clyde’s own story.

Clyde’s family claimed that he told them his associate Henry Methvin was the lone shooter in Grapevine and killed both officers with a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). Bonnie’s mother also claimed that Methvin had “confessed” to her.But these claims, which are unsubstantiated hearsay at best, are contradicted by the available evidence. First, Methvin reported to the FBI that he had been asleep in the car all day while Clyde and Bonnie played with the pet rabbit in the grass and that he was awakened by gunfire. Methvin’s statement jibes exactly with the sworn witness accounts of Schieffer and his two daughters, all of whom consistently stated that there were two shooters and that one of them was female and matched Bonnie’s general description. Second, the theory that there was a lone shooter using a BAR cannot be reconciled with the ballistics evidence from the scene (six large buckshot shotgun shells, five .45 auto pistol cartridges, and only one 30.06 shell casing).

Still, there are those today — a good many — who passionately defend Bonnie Parker and claim that she never fired a gun at any point during the Barrow Gang crime spree. Yet, even a year before Grapevine, a police raid on an apartment in Joplin, Missouri led to another account of Bonnie Parker firing a weapon. This time, as Clyde, his brother Buck, and W.D. Jones, fired on and killed a detective and a constable, Bonnie laid down cover with a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). The fusilade forced Highway Patrol Sergeant G. B. Kahler to seek cover behind an oak tree while the .30 caliber bullets shredded the other side. Patrolman Kahler would later report, “That little red-headed woman filled my face with splinters on the other side of that tree with one of those damned guns”.

Protestations of Bonnie’s alleged innocence are, for the most part, strictly teleological in nature, rather than accurate assessments of contemporary perspectives and evidence. They are also, more often than not, heavily influenced by romanticized popular culture and media depictions of the pair. It is true that Clyde Barrow introduced Bonnie to robbery and murder, activities which she took to with enthusiasm according to numerous eyewitnesses from across the country. In fact, on two occasions Clyde was known to have chastised her for shooting too

quickly, thereby placing them in greater danger of getting caught. Bonnie had long been attracted to and reveled in the criminal lifestyle, and she showed no regard for the gang’s many victims. She wrote numerous letters and poems demonstrating as much, repeatedly asserting her intention to continue their crime spree until death and insisting that she and Clyde would “go down together.”

The truth is that Parker and Barrow were not anti-establishment social anti-heroes standing up against banks and oppressive authorities and sharing their booty with the poor and oppressed like some sort of 20th century Robin Hoods. Their criminal careers predated the Great Depression by almost half a decade, and Clyde only robbed three banks during his eight-year criminal career. Under Clyde’s hair-trigger leadership, the gang scraped by primarily by stealing cars and robbing individuals, families, and small independent businesses struggling to stay afloat, often murdering their prey or officers to avoid arrest. The simple

fact was that they preferred to steal rather than work and to kill rather than risk being caught, as even Clyde’s own sister and mother attested to after his death. At Eastham Prison Farm, Clyde once had a fellow inmate chop off his toe with an ax so he could get transferred out of work detail. Bonnie had dreamed of being a Broadway or movie star (she adored Myrna Loy); front page photos, stories, and her own published poetry provided her the fan base she had dreamed of as an impoverished West Dallas girl. She called the American people “her public.”

But did Bonnie Parker actually pull the trigger at Grapevine? The physical, forensic, and eyewitness evidence from the time indicates that she did. The only sources for claims to the contrary were Barrow and Parker’s families who were obviously not present at the scene and obviously not unbiased; a number of their family members—including both their mothers were soonafter convicted and sentenced to federal prison for aiding and abetting their fugitive relatives.

******

The contemporary evidence of Bonnie’s culpability includes the clear and consistent

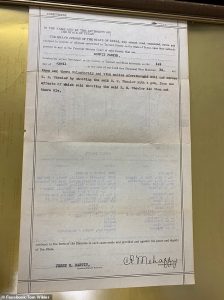

testimony of eyewitnesses to those murders and the ballistics analysis that matched Bonnie’s custom altered shotgun— a weapon she was frequently photographed with that was found in the death car after the ambush. Various published claims that William Schieffer’s testimony was later “refuted” or “recanted” have failed to produce any contemporary evidence to support such contentions. Furthermore, Bonnie Parker was, in fact—and again, contrary to published claims—under indictment for the Grapevine murders before she died; original documentation of this fact recently resurfaced as part of an archival digitization project.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6684095/Texas-court-clerks-indictments-Bonnie-Clyde-old-records.ht

Flawed analysis and facts regarding the Grapevine murders also undermine the claims of Bonnie-apologists, such as assertions that the key eyewitness was “several hundred yards away” from the scene, leading them to erroneously conclude that he could not possibly have made a reliable identification. In fact, he had been as close as 10 yards to the killers at least at one point earlier in the day, and was—along with his two daughters—only 100 yards distant at the time of the murders. The three Schieffers provided investigating officers, the press, and later in court, consistent and detailed descriptions of the shooters and their activities

leading up to and during the crime. As the people who were present the longest, closest to, and had the clearest view of the scene, their key eye-witness accounts should not be discarded in favor of claims by those with dubious objectives who were not present.

Finally, the focus on disputing Bonnie’s role in Grapevine ignores her lengthy and violent criminal career: at least ten other shootings, two jail/prison breaks, eight to ten kidnappings, and more than a dozen armed robberies. Her crimes left six more men dead and eight wounded, and left widows and children to survive without their husbands and fathers in the midst of the Great Depression.

Arthur Penn’s celebrated 1967 film, a well-deserved cinema landmark, used some real-life names but was never intended to document the real-life crimes and the very real human costs of the choices made by members of the Barrow Gang. Nevertheless, most modern Americans have received what little they think they know about the homicidal duo—on which the film was very loosely based—from that work of fiction. Still others have been misled by those seeking to exonerate Bonnie out of some misplaced sympathy, often influenced by an antiestablishment narrative.

Whatever the motivation, the effect is to erase the experiences, perspectives, and memory of the many victims and their families, thereby compounding the injustice inflicted upon them. Friends and family of Marie Tullis report that “she was never the same” and never married. In the words of E.B. Wheeler’s widow, Doris, “[P]opular culture…made heroes of the gang who killed my husband . . . . nobody ever thinks about those of us who were left behind.” Doris

lived on, to the age of 96, but “the anguish never ended.”

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Dr. Jody Edward Ginn is a former law enforcement investigator and U.S. Army

veteran who works as a historical consultant to museums and educational

institutions, and is an adjunct professor of history at Austin Community

College. Ginn has authored numerous publications on Texas history topics,

including “Texas Rangers in Myth and Memory,” in Texan Identities…(UNT

Press, 2016). Ginn’s latest book, East Texas Troubles: The Allred Rangers’

Cleanup of San Augustine (OU Press, 2019) arrives in bookstores in August